INTRODUCTION

Some members of the trial bar have taken a keen interest in a model of trial advocacy that features manipulating jurors by fostering fear. What is this model? It claims you can predictably win a trial by speaking to, and scaring, the primitive part of jurors' brains, the part of the brain they share with reptiles. The theory may sound intriguing on its face, but advocacy is not reducible to mere technique not only because people are much more than their brains, but because advocacy is as much art as science. (If science is relied upon, we think it should be good science, not pop science which presents the brain anatomy incorrectly.) To reduce the human being to a body organ, even the brain, disregards the value of the reflective mind – something no reptile possesses. From time immemorial we have used imagination and supporting evidence in narrative to persuade. A reptile hears no human story. It reacts as a coiling rattlesnake or a slithering lizard. To equate men and women serving on a jury with reactive sub-mammals is both offensive and objectionable. Bringing together decades of experience, research, and insights in the law, healthcare, social relationships, and narrative we posit an alternative viewpoint for lawyers interested in reevaluating the wisdom of 'reptiling' the jury.

As editor of the ABA's Law Practice column "Reading Minds," Stephanie West Allen asked lawyers to recommend the book that most influenced them professionally. Only one book was consistently recommended: To Kill a Mockingbird. Lawyers said the book reminded them of the best that they should be when working in their chosen profession; they mentioned such qualities as respectful, honest, compassionate, of service.

The legal profession's foundation is built on such core values. Despite the bad press and unflattering jokes, most of the Bar are ethical people who endeavor everyday to do what is right. Although the definition of right is not always clear, most try to make wise decisions. But litigators are busy. Their schedules overflow. Sometimes they do what seems appropriate without weighing the broader implications. Sometimes they receive poor advice and follow it without discernment. When these conditions prevail that may hamper a lawyer's good judgment, it is time to take a wisdom check. Lawyers may want to step back and ask if what they are doing is consistent with their wisest professional selves. Specifically, as related to this article, do they want to follow the reptile model.

The legal profession's foundation is built on such core values. Despite the bad press and unflattering jokes, most of the Bar are ethical people who endeavor everyday to do what is right. Although the definition of right is not always clear, most try to make wise decisions. But litigators are busy. Their schedules overflow. Sometimes they do what seems appropriate without weighing the broader implications. Sometimes they receive poor advice and follow it without discernment. When these conditions prevail that may hamper a lawyer's good judgment, it is time to take a wisdom check. Lawyers may want to step back and ask if what they are doing is consistent with their wisest professional selves. Specifically, as related to this article, do they want to follow the reptile model.

Although a lawyer's good judgment may suffer for many reasons, the reasons are not always discreet, particularly when considering the decision to follow a consultant's advice. He or she may take a consultant's advice without adequately evaluating it due to lack of time, lack of attention, or simply because the advice seemed compelling at the time. Regardless, sometimes a lawyer may want to reevaluate the advice of a consultant regardless of why the advice was initially accepted as valid.

Some trial consultants are advising lawyers to speak to juror's reptile brains, to persuade through fear. When litigators think through the implications of such behavior, some if not many may reevaluate the advice and consider better options. In this article, we share a few points about "reptiling" your next jury to assist the reader in a fully-informed wisdom check.

A BRIEF CRITIQUE OF REPTILE THEORY

1. Basic Assumptions of Reptile Theory Are Incorrect

First and foremost, the basic neuroanatomy presented in some advisors' reptile theory is incorrect. Reptiles do not have fear; they rely on pure habit and instinct. Fear, especially learned fear, emanates from the limbic system, which exists only in mammals. Reptile fans may say, "Who cares about the anatomy if the techniques work?" For us, the mistake triggers threshold skepticism. If reptile consultants are inaccurate about this basic principle, what else in what they put forth may be inaccurate?

2. The "Predictable" Fear Response Is Unpredictable

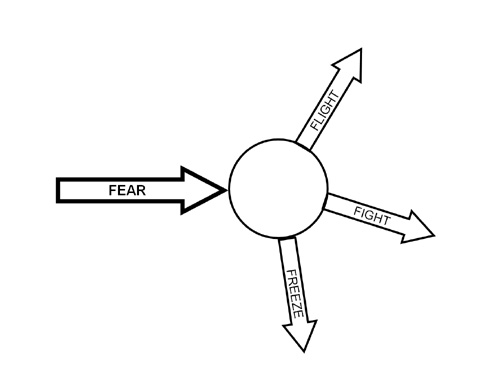

Jurors' brains and minds are not monolithic; their reactions and thought-patterns are diverse. We know that a person will typically respond in one of three ways when frightened. They may fight, flee, or freeze. Obviously, a juror is not likely to flee from the courtroom but her attention may wander or disappear altogether. We are not able to know which response a given juror may have. To gamble on fear in the courtroom is dangerous. It is not predictable.

Below is a diagram that represents this gamble. If a pool player shoots the cue ball towards another ball, that ball can go in several directions. Likewise if a lawyer leads the jury into fear, the results he or she can get are scattered. The result can be flight, freeze, or fight, or one response followed by another. We say forget the balls, get off the pool table, quit the games.

A reptile devotee may argue that the model allows one, using the pool analogy, to be a more accurate pool player. We disagree. You cannot call the pocket using the model. You simply do not know where the fear will go.

3. Jurors Recoil When Disrespected

Scaring jurors may be offensive to some trial lawyers, particularly once they take some time to think through the implications of a threat-based approach. For the wisdom check, a lawyer may ask him- or herself, do I appreciate the jurors' service? Do I see them as animals or human beings? Do I want to speak to their reactive brains or their reflective minds? What about these jurors do I appreciate? In what way am I similar to these people? Is animalizing them consistent with how I want to treat my fellow human beings? Do I come across differently when I see jurors as people as opposed to when I see them as animals? Would I like to be seen as a reptile?

In some sectors of our culture, lawyers have a bad reputation. Animalizing jurors is not going to rehabilitate any lawyer's image, let alone the collective image. To some, animalizing may seem disrespectful to the people who participate in jury service. Are jurors smart enough to sense disrespect? We think they are and it's a rare case that can be won if a jury has been treated without respect.

We doubt that Atticus Finch would have been very impressed with being told to treat jurors like reptiles, or would have followed such advice. Finch treated jurors as people of integrity with the ability to be thoughtful and mindful. He focused on their reflective minds capable of human justice, not their unpredictable reflexive brains.

AN EFFECTIVE ALTERNATIVE: PERSUASIVE NARRATIVE

So, how do you facilitate jurors acting from their reflective minds, not their reactive brains? How do you treat them with respect and integrity and still advocate for your client? One key method is the effective and persuasive use of narrative.

Narrative is the general term for a story told for any purpose. We recognize that narrative is a neutral technique which may be used in service to the reptile. We suggest a particular kind of narrative that attends to people as human beings, not snakes. The narrative we suggest is inconsistent with the reptile technique because it focuses on the reflective mind of the juror.

Research has shown that 'attention density' can cause brain cells to fire together, even if these cells were not "communicating" before.1 Attention density' simply means that the more you focus on a particular thing or idea the more dense becomes your attention as a result of the focus. Thus, wherever you place your attention helps mold or shape your brain.

The critical part of narrative is where you direct the attention of the jurors. In a courtroom we want to use narrative in the way that will help guide jurors to our side of the story. Fear-based narrative directs attention in an uncertain and unpredictable manner while thoughtful narrative directs attention toward action grounded in the reflective mind. Narrative shines the mental flashlight of attention which can reconfigure the brain and change behavior.

In short, narrative is 'attention choreography': narrative directs the attention of the juror in ways we suggest are consistent with the respectful aims of treating jurors as the human beings they are. While narrative can be used for whatever purpose you want, we suggest a human-based narrative.

As far back as there have been stories, there have been stories about disputes. One is about the baker who sues a poor man for standing outside his bakery and smelling rolls he cannot afford to buy. The judge agrees that the poor man may have stolen the smells but for the verdict he rattles some coins in his hand and tells the baker to be satisfied with the sound of money as his compensation. Can you sense the fairness in the judge's decision? All we did was tell you a story.

1. Narrative Provides A Pattern For Understanding

Whenever we hear or read a story, we journey with the teller into the virtual reality of the story being told. The closer the story is to the struggles and outcomes in our real world, the more likely we are able to be absorbed in this virtual world, and the more likely we are to identify with the characters and how the outcome affects them.

Likewise, in a courtroom in the midst of a heartfelt story artfully told the jurors end up collaborating with the attorney to design the outcome that the attorney has in mind. How does that happen? In order to conserve energy the brain seeks patterns. Part of that pattern-seeking process is looking for information based on what it already knows or recognizes. In fact, if the attorney does not hook the new information of the case into the older or existing patterns in the juror's brain, the brain will reject the information. If the brain rejects the information, the message will not be heard. A well-constructed narrative is one of the surest ways to be certain your message heard.

2. Narrative Multiplies the Power of Human Stories

"If we cannot envision a better world, we cannot create one." -Alex Grey

The reptile model of leading with fear to persuade disregards the unique perspective and contributions of each individual. If the lawyer chooses to lead with fear he or she rejects the opportunity to harness the empathy and powers of the individuals who will go on to deliberate the case.

Stories play several roles in achieving justice. As in everyday situations, jurors weigh the significance and accuracy of the competing accounts by comparing them to their own repertoire of stories about how people behave and should behave. Jurors continually ask questions about the differing versions of the stories they hear in the courtroom and react based on how each relates to their own stories.

•How is a given story like others in their world view?

•How are the stories consistent or inconsistent with how they experience the world?

•How are the stories like their expectation of how things ought to be?

•Is this how people and entities behave? What is the same about this behavior and my experiences? What is different?

•And how does each of the stories intersect with the law?

The skillful attorney knows it takes empathy to imagine where those you are trying to persuade are coming from, to anticipate their questions and arguments before they make them. The skillful attorney knows that a thoughtfully crafted story using language with passion, power and precision will address human assumptions underlying the questions and arguments. In short, the skillful attorney knows how to find common ground on fundamental concerns, and persuade based on individual meaning in line with the desired outcome.

The skillful attorney knows it takes empathy to imagine where those you are trying to persuade are coming from, to anticipate their questions and arguments before they make them. The skillful attorney knows that a thoughtfully crafted story using language with passion, power and precision will address human assumptions underlying the questions and arguments. In short, the skillful attorney knows how to find common ground on fundamental concerns, and persuade based on individual meaning in line with the desired outcome.

Yes, 'safety as survival' may be a fundamental concern. But it is one of many. And it is this 'one size fits all' approach that may be destructive or, at the very least harmful when not thought through. If lawyers must reduce humans to something, reduce them to humanity over reptile.

3. Narrative Focuses Juror Attention

Trials present a lot of scattered pieces of information. It is a remarkable process when you step back and consider what we demand of each juror: comprehend, sort out, compare, and collaborate. Jurors pick up the pieces of scattered evidence and construct those pieces into narratives. Each juror evaluates the narrative on two levels: first, a personal comparison with stories they know and have constructed from experience, logic, bias, family, culture, and myriad other individual influences and then a collective comparison with the stories of the other panel members. Yet, a verdict based on thoughtfully chosen narrative is a process of each juror's perceptions coming into sharper focus through the jury's decision-making process: individual input filtered through a group decision.2

4. Narrative Generates Group Identity

"Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful concerned citizens can change the world. Indeed, it's the only thing that ever has." -Margaret Mead

We are troubled by the thought that lawyers have not considered the implications of what it means to reptile a case, to reptile a client, to reptile a jury. (Although 'reptile' is not a verb, many followers of this model have transformed it into one.) We believe that this approach comes dangerously close to manipulating jurors for a base reason; because the lawyer was offered code words that are supposed to trigger fear. And, if that is accurate does the end justify the means? Absolutely not.

We know from research and experience that each individual in a group hears the same story differently. Despite the individual isolation of hearing the story, narrative unites and generates a sense that individuals hearing the story are connected. In fact, the group will be able to agree on the meaning of the narrative and its 'moral'. The group unites in a common purpose and the effectively presented narrative helps jurors develop a group identity and collective momentum toward a consensus decision.

If the jury is driven by fear (or bias or self-interest for that matter) the jury cannot be counted on for a fair decision. You have got to give them their due, and give the process its due: the jurors will arrive at their decision because of the way they collectively sort out and agree upon the competing narratives. Otherwise, why try cases to a jury at all? A neutral, detached jury with the combined forces of individual and group perceptions is the foundation on which we rest our belief in fair decision-making.

5. Narrative Motivates Action

"Only by connecting to a cause larger than oneself can true satisfaction be realized." -Kate Loving Shenk

One of the ways we remind each other about how we have made a difference is to tell each other stories about times when we have been instrumental in achieving justice. In March of this year, New Yorkers again told the story of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, a disaster which killed upwards of 146 young immigrant women working in a sweatshop that caught fire. Locked doors barred escape from the raging inferno. Fire truck ladders could reach only a few stories. Many women flung themselves out the windows rather than burn to death.

The owners were indicted on charges of manslaughter. The defense blamed the dead girls and women. After deliberating for two hours the jury returned a verdict of not guilty. Public outrage over the decision led to the creation of a Commission to investigate working conditions in New York factories. In turn, the Commission's recommendations led to thirty-six new laws in three years which reformed the state labor code. They called it "the Golden Age of factory reform."

How did this happen? The sheer power of citizens brought about the changes:

"Out of that terrible episode came a self-examination of stricken conscience in which the people of this state saw for the first time the individual worth and value of each of those 146 people who fell or were burned in that great fire…We all felt that we had been wrong, that something was wrong with that building which we had accepted or the tragedy never would have happened. Moved by this sense of stricken guilt, we banded ourselves together to find a way by law to prevent this kind of disaster….It was the beginning of a new and important drive to bring the humanities to the life of the brothers and sisters we all had in the working groups of these United States."3

6. Our Core of Moral Advocacy

"The great instrument of moral good is the imagination." -Percy Bysshe Shelley

Human beings are ethical creatures. If you have ever been nagged by a guilty conscience, it is your sense of ethics speaking. That sense of unrest gives rise to wonder: what am I to do in this or that situation to move outward beyond selfishness to the larger ideas of community?

And so we are saddened that a core of moral advocacy leading the profession may be threatened by a push toward snakes and fear. We are disappointed that when one of our legal brethren looks out into the venire panel they see neither humans nor allies but row upon row of triangle-headed reptiles.

Instead, what would advocacy be like if we employed the imaginative capabilities of narrative to help us do right by another? Imagination and narrative are necessary in the world of law. Stories, lest we forget underpin the very construction of the law.

Changes in the story of American life are reflected in changes to legislation and the law. As our culture has changed the laws have changed along with the culture. We can cite a few examples such as civil rights, human rights, the right to vote, workplace security, to name a few. Only when the story of America changed did the law follow along. What is the story you are telling to shape the law, to advance the story of American life?

CONCLUSION

We would like to leave you with this story. In the Protagoras, Plato tells how it was that humans came by moral sense. Two gods were given the task of distributing qualities to each of the animals. Epimetheus gave the best of the qualities to the animals – he had forgotten about the humans. When Prometheus came to check up on how the task was going he found that man had been left naked and defenseless. To help make up for the mistake of oversight, Prometheus stole fire and the mechanical arts from the Gods and gave them to the humans as a way to compensate them. But it was not enough. The humans were too stupid, selfish and mean-spirited. It was looking like the end of the human race, and then Zeus stepped in. He chose to give humans the one gift they needed for survival and greatness. Zeus gave them the gift of a moral sense. And he made sure that he gave it to each one so that each would share in its saving grace. Then, as now it is not fire or our mechanical cleverness or even manipulation that has distinguished us – it is our moral sense.

Seven Tips For Creating the Motivating Story

1. As you work through the discovery process, always be asking yourself, "Apart from my client's injury, what is this story really about?" Better yet, draw your story to see the relationships between the cast of characters and their actions. Taking a perspective that begins long before your client's injury happened will help you begin to connect the dots that will lead you to understanding how the injury was the result of actions.

2. A story is always about a conflict. And the jurors must understand enough about the protagonist, the antagonist and the events to get hooked into the story so they can follow its intellectual and emotional meaning.

3. We expect a story to be about change. In order to meet the jurors' expectation the story must bring to life early on the change you want them to create. This requires you to set up a bridge from the evidence (content) to the context (what situations or circumstances allowed the event to happen) to the emotionally meaningful story your jurors are already carrying in their heads.

4. We expect a story to have a good ending that is in line with how we would write it if we could. A legal story invites the jurors to write the ending. For them to write the ending you want you must invite them at the outset to leave behind a negative, skeptical frame of mind in exchange for one eager to do something positive.

5. We want to discover the message that tells us about the change we could enact so we can make that change happen. If the change message is clear then narrative will help persuade the juror that the change you want them to enact is easily within their grasp. The more we identify with an outcome the more likely we are to use the group identity that narrative fosters to come up with that ending. The message must be the jurors' own idea because it is meaningful to them.

6. We want to identify with the little guy, with the underdog, with the hero of the story. Much of the persuasive power of any story is built upon the fact that the juror identifies with the protagonist. How is your client in your story like the people who will be hearing that story?

7. Test, test and test again. Only by rehearsing your story will you learn whether it will work with the group of jurors you anticipate will hear and act upon your story.

Author Biographies

Stephanie West Allen, JD, Denver-based speaker and writer, practiced law in California. She presents programs and writes on such topics as self-directed neuroplasticity (changing your brain with your mind), and the neuroscience of conflict resolution. She has been a mediator for over two decades, and was director of lawyer training at a law firm. Her blogs are http://www.idealawg.net and http://www.brainsonpurpose.com.

Jeffrey M. Schwartz, MD, research psychiatrist at the School of Medicine at UCLA, is one of the world's leading experts on human neuroplasticity. In addition to over 100 scientific publications, he is author of The Mind & The Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force, and Brain Lock, the seminal book on obsessive-compulsive disorder. More information about Dr. Schwartz can be found at http://www.jeffreymschwartz.com.

Diane F. Wyzga, RN, JD is an experienced trial consultant based in San Clemente, CA who works nationally on civil and criminal defense cases. Diane specializes in case communication and strategy development, pre-trial focus group research, and developing the legal story from start to finish to best position the client in settlement conferences or the courtroom. You can read more about Ms. Wyzga at her web page [http://www.lightrod.net]

Fear graphic provided by Ted Brooks of Litigation-Tech.

References

1Schwartz, J.M. & Begley, S. (2002). The Mind and the Brain: Neuroplasticity and the Power of Mental Force. Harper.

2Sarat, A. (Ed.) (2009). Stories from the Jury Room: How jurors use narrative to process evidence. Studies in Law, Politics and Society, 49, 25.

3Frances Perkins, Commission member and later Secretary of Labor in the Roosevelt Administration.

Normally in The Jury Expert, at this point you would see responses from ASTC-member trial consultants. We decided for this article, we would ask trial lawyers to respond since this piece is directed at trial attorneys. On the following pages (in alphabetical order) we have responses from Mark Bennett, Sonia Perez Chaisson, Max Kennerly and Randi McGinn.

Response to

Atticus Finch Would Not Approve

by Mark Bennett

Mark Bennett is a criminal defense lawyer in Houston, Texas, where he practices with his wife Jennifer. Mark also writes the Defending People blog, where he writes about "the tao of criminal defense trial lawyering".

I see three productive areas for challenges to Reptile Theory. First, the practical: "Does it work?"

The proponents of reptile strategy try to create in jurors' minds a situation in which their survival is somehow endangered:

Does this mean we take orders from a pea-brained snake? Yes. When we face decisions that can impact the safety of our genes, the Reptile is in full control of our emotions as well as what we think is our rational logic. [Ball and Keenan, Reptile: The 2009 Manual of the Plaintiff's Revolution 19.]

Allen et al.'s first practical objection to Reptile strategy–that the fear response is unpredictable, so that you don't know what you're going to get when you invoke the Reptile in the courtroom–is, I think, their weak point. In the courtroom, at the end of the trial, jurors are limited in their possible responses: they can decide the case in favor of the one creating the danger, or against her. Whatever other effect summoning the Reptile might have, it's likely (if not called to jurors' attention) to increase emotion against the one successfully cast as a danger.

Allen et al.'s second practical objection to Reptile strategy–that jurors will sense Reptile lawyers' disrespect for them (or at least for their better angels) and will recoil–is stronger. Like much persuasion, Reptile strategy is manipulation to which the people being manipulated might well object, if they were conscious of it. People are less susceptible to appeals to their baser instincts when those appeals are called to their conscious attention. People who realize that lawyers are deliberately creating and exploiting fear might well react negatively. It's not a question of "animalizing" jurors, as the authors put it, for human beings are animals too, but of trying to make jurors make decisions based on fear, an emotion that jurors in the courtroom would rather disclaim.

This, I think, points to one half of the best response to Reptile strategy: show the jury how the Reptile lawyer is trying to manipulate them through fear. (Two lawyers in Georgia got some attention doing this recently.)

The other half of the best response to Reptile strategy is to engage the "higher" reflective brain functions, as Allen et al. suggest, with thoughtful narrative (or, as I have suggested, with incongruity and complexity.)

Either Reptile strategy works, or it does not. Even if it can be disarmed through labeling, thoughtful narrative, and laughter, there are enough success stories from personal injury lawyers applying Reptile theory to trials, as well as from prosecutors playing to jurors' fears without putting a name on their methods, that it is safe to say that making people afraid works.

Either Reptile strategy works, or it does not. Even if it can be disarmed through labeling, thoughtful narrative, and laughter, there are enough success stories from personal injury lawyers applying Reptile theory to trials, as well as from prosecutors playing to jurors' fears without putting a name on their methods, that it is safe to say that making people afraid works.

Aside from the practical objections that Allen et al. raise, there are interesting aesthetic and ethical questions relating to Reptile theory in trial.

Fear is never a pretty thing, and scaring jurors to win a jury trial is ugly. In itself this isn't much of an objection to Reptile theory–however we order our obligations as lawyers, our duty to the client certainly trumps any responsibility we might feel to the Spirit of Beauty.

But fear is ugly to us for a reason: our brains didn't evolve to live with it for more than a few minutes at a time. The fear mechanism that Reptile lawyers would exploit evolved to deal with immediate dangers–the prowling sabertooth, the noise in the dark, the snake on the path–that could be dealt with in minutes through fight or flight. We weren't made to be afraid for hours at a time, much less days or weeks.

Chemically, fear involves the production of cortisol, long-term exposure to which is harmful to our health. It raises levels of anxiety and depression, impairs memory, drives blood sugar out of whack, lowers bone density, raises abdominal fat, and may speed Alzheimer's. Building a trial strategy around a physiological reaction that is toxic when it is sustained is unfair to and exploitative of our jurors.

If you had a client who could benefit from your playing to jurors' fears would it matter whether the tactic were nasty or harmful to jurors? Or must the duty to the client transcend these particular ethical and aesthetic considerations? Allen et al. invoke Atticus Finch, who "treated jurors as people of integrity with the ability to be thoughtful and mindful." Finch might well have rejected Reptile theory on grounds practical, aesthetic, or ethical. But then the only time we saw Atticus in trial, he lost.

Response to Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga

by Sonia Perez Chaisson

Sonia Perez Chaisson is a Los Angeles Plaintiffs trial attorney who is often called at the last minute to co-counsel complex civil and criminal cases. She also facilitates cutting edge workshops for fellow attorneys and is a 2003 graduate of the Trial Lawyer's College.

It's challenging to respond to an article when the article misunderstands Reptile trial advocacy and then attacks it on the basis of that misunderstanding. The article blasts the Reptile method as insulting to and manipulative of jurors for being fear-based and disrespectful of jurors. It makes me wonder how familiar the article's authors are with it. Reptile methods lead with justice and the well-being of the community – the two founding fundamentals of western law.

Equally perplexing is the article's argument that the pro narrative approach is an alternative to Reptile. Even the authors are conflicted about this; they say, "We recognize that narrative is a neutral technique which may be used in service to the Reptile." I wholeheartedly agree. The narrative method is one of the many time-tested tools for good advocacy — and works well with the Reptile method precisely because it is in itself a Reptilian technique! The article is off-base in proposing the use of story as an alternative to the Reptile. One includes the other, as the Reptile's originators clearly and repeatedly teach.

The article worries that Reptile fans may say "Who cares about the anatomy if reptile techniques work?" True; that's what we say. We care not at all about brain anatomy and solely about whether the Reptile works. As a trial lawyer whose clients depend on me for justice and whose livelihood depends on whether or not I obtain justice and get paid, I care more about whether the Reptile works than about quibbles over labels for brain anatomy. Until the advent of the Reptile and its related methods such as those taught at TLC, we have all seen case after meritorious case "defensed" to death because plaintiffs' counsel, just like Atticus Finch, lacked the tools to reach unfairly biased jurors–a skepticism that comes into civil justice today from years of dishonest propaganda by the insurance industry, corporate interests, and the Karl Roves of the world. We are relieved that we now have something as powerful and honest as the Reptile, and that the research and field testing of it continues.

Reptile works. Atticus Finch, despite good intentions, lost. So an innocent man suffered. Had Finch known Reptilian methods he'd probably have won– and for all the right reasons. The results of Reptilian advocacy–when deployed by trial attorneys mastering it and not merely reading about it and its complementary methods — such as those long taught at the Trial Lawyers College — have restored sanity to an arena poisoned by decades of bogus tort "reform " attacks.

It is disturbing not merely that the article exhibits a misunderstanding of Reptilian advocacy, but that the article dismisses it with little regard to the results and feedback from trial attorneys across the country who are reporting its frequent and unprecedentedly successful results. The dirty tactics, and the power and resources of insurance company giants are now meeting their match. My understanding of the mission of Reptile advocacy is to return justice for civil plaintiffs by enlisting the Reptilian forces of truth, juror empowerment, and positive – not negative – juror motivation. The Reptile is not about fear; it is tort "reform" that is about fear. The only fear in Reptilian advocacy resides within the defense. Reptile advocacy and its complementary methods give to individuals hurt by negligence and to jurors a voice with which they are now, finally, consistently able to speak truth to power.

Response to Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga

by Max Kennerly

Maxwell S. Kennerly is a litigation and trial lawyer at The Beasley Firm in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He represents individual plaintiffs in personal injury and malpractice cases, and represents businesses in breach of contract and fraud cases.

Maybe Atticus Finch wouldn't approve of the "reptile" methodology, but let's not forget: he lost his case. Justice was not done for Tom Robinson.

Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga reference Atticus Finch not once but twice, for good reason: his ghost haunts trial lawyers, civil and criminal. Whenever we grow weak or greedy, Atticus is there, staring at us, understanding but disappointed. He is the archtype of the great lawyer, ethical and empathetic, with an unwavering devotion to duty.

But let us not forget the meaning of Atticus' story. Atticus not only established reasonable doubt that Tom Robinson was guilty, but affirmatively proved that Robinson's accusers were liars. The jury cared not one bit; instead, driven by bigotry — a product of the so-called "reptile brain" — they convicted him nonetheless. As compelling a role model as Atticus is, if we are to accept that he limited himself in his means of advocacy, then he is also a cautionary tale about the downside of imposing such limits on ourselves.

Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga also reference the criminal manslaughter trial of the owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, a case which, too, presents a cautionary tale for trial lawyers. There, two of the most reviled men in New York City, on trial for causing a calamity so horrible the screams of its victims still reverberate ninety-nine years later, were acquitted in less than two hours of jury deliberation.

The reasons for the acquittal are many, but chief among them was the testimony of Kate Alterman, one of the workers on the ninth floor. With minimal prompting by prosecutor Charles Bostwick, Alterman gave a harrowing and uninterrupted account of the fire, of hiding in the toilet, of watching the manager's brother trying and failing to open the Washington Street side elevator door before "throwing around like a wildcat" at a window from which he wanted, but was too afraid, to jump, of watching the ends of her friend Margaret's hair began to burn, of covering her face in dresses not yet burned, of another lady holding Alterman back in a panic, and of running through a door that "was a red curtain of fire" before escaping to the roof.

Defense counsel Max Steuer ignored half of Irving Young's Ten Commandments of Cross-examination — "be brief," "use only leading questions," "avoid repetition," "disallow witness explanation," and "limit questioning" — and asked, "now tell us what you did when you heard the cry of fire." Alterman complied, in virtually the same words she had used before. Steuer asked her to describe it again, which she did, in virtually the same words she had used before.

Defense counsel Max Steuer ignored half of Irving Young's Ten Commandments of Cross-examination — "be brief," "use only leading questions," "avoid repetition," "disallow witness explanation," and "limit questioning" — and asked, "now tell us what you did when you heard the cry of fire." Alterman complied, in virtually the same words she had used before. Steuer asked her to describe it again, which she did, in virtually the same words she had used before.

She had been coached. The jury could not forgive the prosecution's manipulation. As Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga correctly note, "it's a rare case that can be won if a jury has been treated without respect."

I bought a copy of Reptile by David Ball and Don Keenan on the strength of Ball's prior work, Damages, a level-headed and comprehensive text that should be read by every civil trial lawyer. Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga tell plaintiff's lawyers to ask themselves, "apart from my client's injury, what is this story really about?" Reptile provides an answer: at trial, a plaintiff's lawyer's "primary goal" is "to show the immediate danger of the kind of thing the defendant did — and how fair compensation can diminish that danger within the community."

Simple enough, and not particularly novel. Consider how Charles Bostwick closed his criminal prosecution: "Safety and all was on the other side for her and the others, and this safety was kept from [Margaret]. Why? To prevent these defendants, who had five hundred people under their keeping–their lives–from the paltry expense of a watchman." He need only have been in a civil trial and have added a line about compensation to have adhered to the Reptile method, nearly a century before it had that moniker. (One might say he lost his case by being too 'reptilian.')

I still do not understand why Ball and Keenan made themselves a target with such a provocative title or why they made the supposed inner monologue of the reptile one of the recurring themes of their book. The advice given in book — primarily straightforward ways to keep a case focused on "the immediate danger of the kind of thing the defendant did" — would have been just as useful, and a lot less controversial, without the pop science "reptile brain" references. Indeed, I doubt that Ball and Keenan would quarrel with Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga's conclusion that "advocacy is as much art as science." Apart from the "reptile" hook, Ball and Keenan thankfully spend little time attempting to ground their advice in science. It's art, pure and simple.

In the field of advocacy, little has changed since the publication of Artistole's Rhetoric two and a half millenia ago. "There are, then, these three means of effecting persuasion. The man who is to be in command of them must, it is clear, be able (1) to reason logically, (2) to understand human character and goodness in their various forms, and (3) to understand the emotions-that is, to name them and describe them, to know their causes and the way in which they are excited." Whatever label we give our particular means of exciting the emotions — such as Ball and Keenan's "reptile" or Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga's "moral sense" — we must be careful not to miss the forest for the trees.

Advocacy is an art driven by language and emotion, not a science driven by data and testable hypotheses. Although it is always folly to attempt to manipulate a jury, advocates must remain open to all of the rhetorical tools available to them, and must adapt to the case at hand, sometimes by focusing on "the immediate danger of the kind of thing the defendant did," sometimes by crafting a "persuasive narrative" through "attention choreography," and sometimes by mixing those approaches.

As Atticus Finch said, "The one place where a man ought to get a square deal is in a courtroom, be he any color of the rainbow, but people have a way of carrying their resentments right into a jury box." Courage, he said, is "when you know you're licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what," and he saw Tom Robinson's case through by trying to focus the jury on "the immediate danger" of his accuser's perjury and of convicting an innocent man.

Maybe Atticus was a "reptile" after all.

Response to Anti-Reptile Article

by Randi McGinn

Randi McGinn is a verbal alchemist who takes client's life stories and, if she tells them truly and well, turns them into justice. She is the senior partner in a five woman, one man law firm in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

The world of trial practice is not a choice between "Reptile-lawyers" and "Narrative lawyers." Good trial lawyers should learn all they can about both approaches and use the colors from each of the two crayon boxes appropriate to the individual case facts. Rather than be fearful of the "new" ideas in the research on how unconscious primitive emotions drive a juror's decision-making, lawyers can incorporate that knowledge into their narrative approach to telling the story of the case.

The research on decision-making does not espouse simply punching the "fear" button. Such an elementary approach to a complex subject is like shaking up a carbonated soda bottle and hoping it will only spew on your opponent, rather than drenching you both. Fearful people do not always make rational decisions and, instead of going where you want to direct them, sometimes do a lemming run over a cliff or reject the political party that got them so worked up and create a Tea Party.

The research on decision-making does not espouse simply punching the "fear" button. Such an elementary approach to a complex subject is like shaking up a carbonated soda bottle and hoping it will only spew on your opponent, rather than drenching you both. Fearful people do not always make rational decisions and, instead of going where you want to direct them, sometimes do a lemming run over a cliff or reject the political party that got them so worked up and create a Tea Party.

The better decision-making approach is to appeal to our sense of survival – both as individuals and as a community. This means creating a narrative in which the juror can imagine that they or their family members might be in the same "zone of danger" which caused harm to the injured person — a narrative story which ends with the juror as a hero or shero, making themselves and their community safer.

One need not choose between these two approaches. The best story for a juror is always the one which quickly becomes about themselves.

Response from the authors

Recently, one of us took a road trip north on the 5 freeway to Half Moon Bay, California. The 5 Freeway passes through some of California's prime growing fields. Here is where you will see the California Aqueduct running along in its concrete cradle.

Some of the fields bordering the 5 Freeway were lush and green; others were dry and dusty. Every few miles a sign was pegged into the ground. The signs read the same: "Congress Created Dust Bowl." Could it be? Did Congress create these acres of dirt? Perhaps it was environmentalists? Or politicians? Or even subsidized farmers? There was no way to know. Driving past those signs was a single story: "Congress Created Dust Bowl."

Narrative is the way we relate to each other. When we are our best selves narrative is used to help us see each other more clearly, bridge the divides and, most importantly, begin to solve our problems while fearing one another less.

And yet, narrative can be used as the big lie. This is the danger of the single story. Single story narrative is the same as the big lie when it is a narrative based on fear, manipulation and limited vision. Hitler was a masterful storyteller. His single story was the rise of the (useful) Aryan race through execution of the (useless) Jews.

Our lives, our cultures, are composed of many overlapping stories. And the danger is that if we hear only a single story about another person or entity, we risk a critical misunderstanding. The single story robs people of their dignity because it assumes only one approach. The single story is not untrue so much as it is incomplete. A single story is unworthy of belief and untrustworthy because it is incomplete.

Likewise, when we demand people to follow us we disallow the opportunity for thinking men and women to participate in problem solving. By making demands on jurors to behave in a certain way we treat them as if their passions, their drives, their needs can be manipulated. Conversely, when we invite jurors to collaborate with us in coming to a resolution, we become partners.

It is this very notion of entering into a collaborative relationship with the jury that drives us to recommend viewing jurors as allies not enemies. We invite lawyers to be willing to look at the jury of peers as thinking thoughtful people who desire to collaborate to a verdict in a community of truth.

One reviewer commented that narrative works when it embraces the story of the community. We agree. And the story of a community can be based on shared common views that are courageous, collective, and creative. When we fully integrate a heartfelt story artfully told with the power of thoughtful advocacy, civility, and respect for the process of litigation we have not weakened ourselves. Rather, we have earned the right to speak for those who cannot speak for themselves.

And that was the point of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire story: to demonstrate that despite the outcome the people of the community were responsible for the Golden Age of reform in the New York sweat shops. The people of the community saw the lie of the single story that immigrants, especially immigrant girls and women are as fungible as beans in a jar, as disposable as cold ashes from yesterday's fire.

Another reviewer claimed that while a narrative is nice, we need the ugliness of fear as the rationale to win. This same reviewer decried using Atticus Finch as the model because "the only time we met him – he lost." Here's a question: what Negro man living in Alabama in the Deep South in 1933 accused of raping a white woman would have stood a chance at winning? The beauty of this fictional story which has continued to haunt us all these years is that a white man stood up to defend Tom Robinson against all odds. Atticus risked it all. The miracle is that a trial took place before Robinson was lynched. One reason being that Atticus sat up the night outside the jail under the light of a street lamp to keep that mob at bay.

Moreover, it is blatantly absurd to state, as one reviewer did, that "had Atticus known Reptilian methods he probably would have won." Really? In 1933? In Alabama? Where a Negro man in the Deep South was called 'boy'? And the court of justice was carried out by men wearing hoods in the nighttime? The Dream Team of King Solomon, Thurgood Marshall, and Justice John Paul Stevens could not have rescued Robinson in a court of law.

We find it sad and disheartening that several of the reviewers did fault Atticus for not winning. How about recalling what he did do, what he did accomplish, and why his children were told to stand as he passed by. That is the kind of lawyer we are looking for. The one who will be thoughtful toward the Reptile theory and consider what it means to tell something other than the single story of fear.

One may claim that the Reptile has a point to make. Let's keep it in perspective: its claim is fear-based narrative. Its claim is the single story. Its claim is that when lawyers regard their clients, their juries, their opponents as air-breathing, cold-blooded, egg-laying, scaled animals – who by the way do not experience fear – then somehow that combination will make these lawyers better than the legions of tort-reformers who have attacked them.

The writers of the article paid their money for the book and then read it. It is an unfair assumption to "wonder how familiar the authors are with the theory" just because we do not agree with the theory. This is not to say that there are not a few gems of wisdom buried in the book. But they lie dormant under the mud of the overall approach – the danger of the single story.

Moreover, this same reviewer proudly assets, "The article worries that Reptile fans may say 'Who cares about the anatomy if reptile techniques work?' True; that's what we say. We care not at all about brain anatomy and solely about whether the Reptile works." To that we must reply that if lawyers do not care about the science of the theory, they do not care about the facts and if they do not care about the facts they have undermined their own legal credibility.

There are claims that Reptile theory works. But who would introduce that? And where is the evidence? Who has personal knowledge that leading with fear is what sold the bill of goods to the jury? There is no study that says, as one reviewer pointed out, "It works." What works? And how do we know? Short of anecdotal reports there is no proof.

When a lawyer is fully integrated into his client's story, he brings together knowledge and heart. He takes experience and information into the court battle to seek the justice his client lays claim to. Because both sides claim justice. And when it comes right down to it justice is just us creating a narrative that embraces a community, that calls people together to figure out a problem, and to help with redress.

The Reptile theory masquerades as the furtherance of good. We object. To lead with fear returns us dangerously close to the danger of the single story: that unless you are afraid, very afraid, and act on your fear, life as you know it will disappear and you and your loved ones along with it. Enough of fear – we are calling for good and thoughtful men and women who question the integrity of such an out-moded approach.

Paul Scoptur has pointed readers of his blog (Scoptur's Law) to this article: Paul's blog

'Joe Attorney' has done a blog post on this article at Doing Justice blog: Doing Justice blog post

Mark Bennett has done a blog post on this article: Mark's blog post

Stephanie West Allen has done a blog post on this article: Stephanie's blog post

Stephanie West Allen has done a blog post on this article: Stephanie's blog post

This is an interesting exchange. Here is my attempt to put the argument into perspective in four steps.

First, accept the premise that one can’t use linguistic tools (courtroom arguments) to communicate with a part of the brain that lacks language (the ‘reptilian’ brainstem) – I suspect that David Ball, Don Keenan and any devotees of the approach that have considered that part of it, would grant that obvious biological point.

Second, understand that if that first premise is true, then you are not by-passing rationality, judgment or narrative fidelity by using a fear appeal. It is an appeal that, like any appeal, can be made well or poorly; that can resonate with your jurors’ experience or fall flat; and importantly – that can be accepted or rejected.

Third, draw a distinction between “fear,” and adjectives “base,” “irrational,” “ugly,” or “animalistic.” Fear isn’t necessarily the dirty word that West Allen, Schwartz and Wyzga make it out to be. It is one of many human motivators, and sometimes fear is rational. Think of a world in which decision-makers in large corporations can get away with actions and choices that tangibly harm many individuals. Or think about a world in which the clever, lucky or powerful can commit crimes with impunity. I trust neither is too much of a stretch. Aren’t those worlds that are to be feared, and isn’t that fear a _rational_ and even a _moral_ response? Remember step two – there isn’t anything about a fear appeal that magically skirts the brain’s cognitive powers and there is nothing about a fear appeal that automatically defeats our habits of placing events in a moral narrative universe. What the authors appear to be criticizing isn’t necessarily a fear appeal but a bad, unjustified, or insulting fear appeal. Rightly so, but that shouldn’t be confused with an attack on a “reptile” persuasion approach per se.

Fourth and finally, acknowledge that the ‘Plaintiff’s revolution’ is hardly the only force encouraging the use of fear in legal persuasion. The approach ought not be read without the context of the tort reform movement’s reliance on exaggerated images of a “litigation crisis” and a “sue-happy culture” that is jeopardizing what we hold dear. In that context, there is a logic to showing “the immediate danger of the kind of thing the defendant did,” and there is a word for it that is simpler than fear: balance.

My comments will somewhat mirror Ken's input as well as the responses within the article. I believe that the spirit and purpose behind Ball and Keenan's Reptile book was misunderstood. Ball has always advocated for telling a story or narrative. His writings in David Ball on Damages specifically states that the presentation should be centered around a story. He states that stories are how humans have learned from the beginning of time and that by starting out with "Now let me tell you a story," you capture jurors' attention. He even advocates for shaping the story to meet each individual juror's perception of the issues. By listening intently during jury selection and by, hopefully, conducting mock trials beforehand, attorneys should have an idea of what terminology will resonate with jurors and what story to tell for that specific case. The Reptile was not meant to override those basic principles. Instead, it adds just one element to the story – and one to which I do not believe is offensive. Fear is just one emotion, similar to anger or sympathy (which the authors advocate using!). The difference is that fear does override other emotions at times. The defense bar has used fear for years in creating the tort reform attitudes we see in the courtrooms today. Is it okay for them to use it to create such a hugh advantage that truly valid plaintiffs' cases often cannot get compensation from today's jurors and yet for plaintiffs not to try to use it to gain some footing back? It is no more of a tactic than showing "day in the life" videos to gain sympathy.

Further, the authors never mentioned the fact that in certain circumstances, such as when confronted with fear, humans use mental shortcuts (heuristics) to come to a decision. The authors suggest using a narrative without fear which utilizes the less primative parts of the human brain and asks people to more deeply examine and process the evidence. The problem with this is that the defense has already invoked fear through tort reform propaganda and therefore, jurors are already not processing information in the thoughtful manner the authors wish for. They are already taking mental shortcuts to save the community and therefore themselves from further harm from what they are led to believe are the many frivolous lawsuits. If plaintiffs do not have an equal way to fight back and to access that primative part of the brain which uses mental shortcuts, they automatically lose.

As for jurors feeling disrespected and duped, that is part of the art of storytelling and presentation. It has to be genuine and delivered with a certain tone of voice and demeanor. If invoking fear itself made people feel angry, then tort reform attitudes would not be at such a high right now. The defense has successfully used fear without invoking anger from people for feeling manipulated. It is all in the delivery.

Ultimately, Reptile is about the art of advocacy and doing what is best for the client. It is not about creating only fear, but of showing the danger of the defendant's conduct and how that can affect the community as a whole. Fear is one part of the story, but not the whole story.

Ken,

I am not a devotee of the approach, but I can't grant your premise.

First, students of hypnosis, NLP, meditation and a hundred other disciplines know that words can reach us in ways that we don't consciously register.

Second, look out! Someone shouted that near me the other day, and I flinched, ducked, and crouched. Why? I guess it was because my higher brain processed the words and passed them on down the line as something that needed to be acted on instinctively, rather than pondered.

Mark,

My point is not to deny the role of unconscious reactions, but to argue that when reactions stem from language, they don't by-pass cognition. If someone had shouted "peanut butter!" near you, you may well have ducked as well, because you are reacting to the shout more than to its linguistic component. My point is that when attorneys make arguments that appeal to safety and security, thet may well be effective, rational, and moral appeals (there is nothing dirty about a fear appeal), but that is simply Maslow's heirarchy, not some kind of direct line to the reptilian brain.

Jessica – good comment.

The Reptile theory, as I understand it, is not about placing the jurors in fear, it is about framing the case in such a way that the jurors can see the defendants conduct as a threat to their own safety or the safety of others. It is not about "scaring" the jurors, but rather about puttin the case before them in such a way that they can see the danger involved in the choices the defendant has made.

I respectfully suggest that TJE was putting the cart before the horse when it put forth the critique of the so called "reptile theory" with out first including at least some excerpts from the Ball/Keenan book setting forth their premises (unless they were included in earlier TJE issues that I havent read). As Montgomery Delaney commented " The Reptile theory, as I understand it, is not about placing the jurors in fear, it is about framing the case in such a way that the jurors can see the defendants conduct as a threat to their own safety or the safety of others." Based on my understanding of the Ball/Keenan book this is a fair, succinct summary of the "theory." As such, my question is "what is NEW about this approach?" Hasn't this always been the underlying plaintiff theme in product liability, medical negligence, product liability litigation and a host of other types of personal injury cases? Haven't plaintiffs attorneys rightly been attempting however directly or indirectly use fear of future bad acts on the part of defendant corporations, doctors etc. to persuade juries to send a message to the community with their verdict? I think the the TJE authors and perhaps many of the critics of Ball/Keenan's approach are reacting more to dramatic language and the sinister image of "the reptile" used by these authors as they hype their so-called "new" theory rather than its underlying principle. But to me (and perhaps to others who know Ball at least) this is just "vintage Ball" who has proven rather successful at selling his books– all of which contain pithy, flamboyant and entertaining rhetoric that is generally non-academic, easy to ready and appealing especially to a certain genre of attorney–trial attorneys! Any successful trial lawyer knows that it's the artful combination of narrative, rhetoric, personality and demeanor of witnesses and attorneys, and yes, finally FACTs that work to persuade jurors –not the simple employ of the current "flavor of the day" new 🙂 trial technique. The Georgia case referenced in the TJE article above just goes to show how smart opponents can use the "gimmick" aspect of the so called new "reptile" theory to undermine it's effectiveness. And Im sure we will read about more examples like the Georgia case in the future. When I emailed David Ball earlier this year to get his reaction to the raft of media coverage on the Georgia case that detailed the defense calling out of the theory and their reading direct quotes from the book, he was predictably unpreturbed stating to effect "who cares, it sells books!" Judging from the slick new brochure distributed recently by AAJ advertising this book as well as other Ball books and those of other authors, this is the main point–come to our seminars, hear our cutting edge theory, buy our books–learn some new tricks–and by the way raise money for AAJ. And I am not criticizing–it's a legitimate way to raise funds for individual authors and organizations, but that's what it is. Certainly the visceral adverse reaction of humans to anything reptilian is well known. To me advocating "reptile theory" just reinforces historically cynical views of the plaintiffs bar, (and if I were a plaintiffs attorney I surely would not want publically to proclaim myself as an advocate of the theory). However, many plaintiffs attorneys say "it works!" I still fail to see what "it" is that is any different. I would be interested in reading some cases examples where the "theory"was employed that sets forth concretely what the attorney did differently based on "reptile." Finally, I agree with others who pointed out that using Atticus Finch who lost a noble cause as a central image for their critique was not an effective image to use to persuade litigators.

I'm as great an admirer of the noble character of Atticus Finch as anyone, but let's not forget that Atticus lost the case, his client committed suicide, and his daughter nearly got killed by the man that Atticus humiliated at the trial. Maybe Atticus was serving a larger purpose by shaming the jury and exposing their racism, but he certainly did not triumph in the short term, and arguably he did not serve the trial lawyer's highest ethical obligation, which is to zealously represent his client. If he could have saved his client without challenging the unjust social structure that the jury ultimately chose to uphold, perhaps he would have served his client's interests better. And maybe an appeal to the jury's more reptilian instincts would have worked better than appealing to their better natures. Perhaps a more overt appeal to the fight or flight response would have resulted in a hung jury.

But it's probably an over-simplification to think that we can choose between an appeal to the reptilian brain or to the more highly-developed cognitive areas of the brain. I think you have make both an emotional and a rational argument to persuade anyone of anything.

Stephanie West Allen has done a blog post on this article: Stephanie's blog post

Stephanie West Allen has done a blog post on this article: Stephanie's blog post

I was trying to think of examples of "reptile" argumentation and this video came to mind.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Se12y9hSOM0

In the context of this article, I am struck by the notion that every good story includes some kind of "problem." If there is no threat, no fear, no obstacle… who cares?

Isn't the locus of power in the "reptile" tactic (on the plaintiff side) to recognize and measure the negative condition associated with the claim? The damage?

With or without the "reptile" moniker, isn't harm, a negative condition or threat to social well-being the primary component of every legal action?

Ms. Chaisson is on the mark in observing that the authors, to a large degree, misconceive Reptile Principles, and certainly misapprehend how they are actually applied, as just one facet of the narrative, in practice.

At a jury draw in a case of mine a few weeks ago, one of the panel members was responding to another panel member's comment that the defendant's conduct — not paying attention and driving into the rear-end of the plaintiff's car — was "just an accident, not really negligence." She disagreed with the other juror, commenting, "It could have been anybody that the defendant drove into, a child crossing the street, a mother pushing a stroller."

Exactly.

This juror was viewing what the defendant had done not as an isolated "accident," but as the type of conduct that is a peril to public and community safety.

This came from the jury, organically. This was not the product of some lawyer trying to manipulate, or turn the jurors into "reptile." And it was not contrived "fear-driven" thinking. Instead, this juror was voicing common, deeply ingrained, but honest and very human, safety-driven concerns about community and public safety. This was, for her, part of the story. As Eric Oliver teaches, there is no single "case story," but at least 12 different stories (for each individual juror). To discount or disregard this part of the story is to disrespect and discount this very real, human response, one that does indeed affect, the decision-making of at least some jurors — including those for whom "tort reform" holds the strongest appeal.

To me, that is in large part what The Reptile concepts are about — discovering and tapping into one (but certainly not the only) important part of the story or any civil injury case for at least some jurors, of how holding the defendant fully accountable for dangerous actions is important for community and public safety.

This does not requires viewing or attempting to turn jurors into "reptiles" — that's not what Ball and Keenan are advocating. But I do think that if we ignore (as many of had in our injury cases for so many years) the strong and deeply human drive to keep ourselves, our families, and our communities safe, we are ignoring, and ultimately disregarding one important element of the story and narrative of the case. And we do so at our client's peril.

Ms. Chaisson is on the mark in observing that the authors, to a large degree, misconceive Reptile Principles, and certainly misapprehend how they are actually applied, as just one facet of the narrative, in practice.

At a jury draw in a case of mine a few weeks ago, one of the panel members was responding to another panel member's comment that the defendant's conduct — not paying attention and driving into the rear-end of the plaintiff's car — was "just an accident, not really negligence." She disagreed with the other juror, commenting, "It could have been anybody that the defendant drove into, a child crossing the street, a mother pushing a stroller."

Exactly.

This juror was viewing what the defendant had done not as an isolated "accident," but as the type of conduct that is a peril to public and community safety.

This came from the jury, organically. This was not the product of some lawyer trying to manipulate, or turn the jurors into "reptile." And it was not contrived "fear-driven" thinking. Instead, this juror was voicing common, deeply ingrained, but honest and very human, safety-driven concerns about community and public safety. This was, for her, part of the story. As Eric Oliver teaches, there is no single "case story," but at least 12 different stories (for each individual juror). To discount or disregard this part of the story is to disrespect and discount this very real, human response, one that does indeed affect, the decision-making of at least some jurors — including those for whom "tort reform" holds the strongest appeal.

To me, that is in large part what The Reptile concepts are about — discovering and tapping into one (but certainly not the only) important part of the story or any civil injury case for at least some jurors, of how holding the defendant fully accountable for dangerous actions is important for community and public safety.

This does not requires viewing or attempting to turn jurors into "reptiles" — that's not what Ball and Keenan are advocating. But I do think that if we ignore (as many of had in our injury cases for so many years) the strong and deeply human drive to keep ourselves, our families, and our communities safe, we are ignoring, and ultimately disregarding one important element of the story and narrative of the case. And we do so at our client's peril.

Ken Broda-Bahm wrote: ". . . one can’t use linguistic tools (courtroom arguments) to communicate with a part of the brain that lacks language (the ‘reptilian’ brainstem) . . ."

I don't know about that. If you are walking with your family in a strange and unfamiliar city, and sometime whom you trust explains to you the safest route to get where you are going, this can trigger some pretty deeply-ingrained, and on some level even unconscious, feelings and motivations to keep ourselves and our family safe. If given two routes, one that will help ensure our safety, and one that is more dangerous, we will usually pick (decide on) the safer route.

Ms. Chaisson refers to unfairly biased jurors poisoned by decades of lies told by "the Karl Roves of the world" and then feels relief that finally plaintiffs can win justice by utilizing the same fear-based "Rovian" tactics against corporate interests. This describes perfectly the downward spiral of emotion-based advocacy – not only in the court but throughout civil society. Though not intrinsic to the authors' piece, what I hear them saying is that they long for a return to thoughtful, fact-based analysis of legal questions. After all, this analysis and decision making is taking place in a court of law where emotion must always take a back seat to logic and reason. Any other method of ascertaining justice does not serve a nation of laws.

We all have a duty to guard the foundations of our democracy. Do lawyers bear a special responsibility in the way they conduct trials? I would argue that the answer is yes, they do owe a special duty to the truth and to the law. They are first and foremost duty-bound officers of the court – before they are advocates, not after. What happens in the courtroom should not be a reflection of what passes for discourse in civil society. Rather what happens in the courtroom should serve as a guide for how we ought to conduct ourselves in civil society.

Regardless of any high ideals we may or may not feel, in my experience, a party invoking emotion is admitting the weakness of their case. This is true whether it is the plaintiff or the defendant who makes such an appeal. "If the facts are against you, argue the law. If the law is against you, argue the facts. If the law and the facts are against you, pound the table and yell like hell." (Carl Sandburg) I think that jurors inherently understand this premise as it reflects our everyday experience.

In one recent EDTX case, plaintiff's counsel compared my client to Karl Marx. He probably thought that was a safe bet in this ultra-conservative, Fox-and-Friends community. But the appeal came off as desperate and mean. The jury was visibly shocked and emitted exclamatory gasps. Ultimately, the plaintiffs lost their case because, I believe, the facts were against them. The plaintiff's used emotional appeals throughout the trial. Most of them far more subtle than the Marxist remark. But the jury didn't buy it. It didn't work. Had the trial lasted only a day or two, perhaps fear would have been a better tactic. Over the course of a week and a half, though, no jury can easily maintain that state of emotional arousal. Sooner or later, the higher analytic thought processes take over.

Remember that an advocate is not only telling a story they are also a character within that story which continues to unfold until the verdict is rendered. Jurors will not only try to fit the narrative you tell within the framework of their own experience. They are also watching the advocates for clues as to whether the storyteller is truthful, passionate or manipulative.

Provoke the reptile at your own risk. You may get bitten.

Stephanie West Allen has done a blog post on this article: Stephanie's blog post

Victoria Ward has done a blog post on this article: Victoria's blog post

I've read Don Keenan's and David Ball's book. I've attended their seminar. I've implemented those parts of their teachings that work for me. In my experience, they are on the right path. I do not ever recall hearing them or reading that they advocate placing jurors in fear of life and limb. David, of all people, has consistently and brilliantly advocated and explicated the use of narrative in jury trials, so it seems to me that the authors have clearly missed the mark in creating a "Persuasive Narrative" vs. "Reptilian" approach to jury persuasion, and, as Sonia Chaisson eloquently explains: "The narrative method is one of the many time-tested tools for good advocacy — and works well with the Reptile method precisely because it is in itself a Reptilian technique!"

Ms. Chaisson goes on to state that: "Reptile works. Atticus Finch, despite good intentions, lost. So an innocent man suffered. Had Finch known Reptilian methods he'd probably have won–" She is absolutely correct, and in 1989, decades after "To Kill a Mockingbird," in the movie "A Time to Kill," from the John Grisham book, her point is brilliantly demonstrated:

Set in Mississippi, the film revolves around the rape of a 10 year old black girl by two white racists, their arrest, and subsequent murder by the girl's father. The film focuses on the father's trial before a jury of all white southern men and women.

In his closing, Jake Brigance (Michael McConaughey) tells the jury to close their eyes and listen to a story. He describes, in slow and painful detail, the rape of a young 10-year-old girl, mirroring the story of Tonya's rape. He then asks the jury, in his final comment to imagine the victim as a white girl.

This is a stroke of pure Reptilian brilliance, for it instantly crystallizes to the white jurors that this is not just about a black man on trial for murdering some white men (who happened to have raped his child), rather, it forces the jurors to see that this was not just some black girl, it requires that they not distance or insulate themselves and their families from the horror of the rapists' acts, and they realize that the only way to protect themselves, their own children, (and the community), from similar atrocities was to find the defendant not guilty.

I'm sure Don Keenan and David Ball would agree that Brigance woke the Reptile in the minds of the jurors, which basically mandated the outcome. Fiction? Yes, of course…but so was Atticus Finch; a great man…a wonderful champion of moral rights, and a fabulous example of the force of the "Persuasive Narrative." But as Ms. Chaisson correctly points out, Atticus lost, but Jake Brigance won…both using persuasive narrative, but Brigance won because he had the force of and foresight to use the Reptile.

Fiction? Of course…but you can't argue with success!

STEPHANIE WEST ALLEN, J.D. wrote her beliefs regarding “The Reptile” theory from Keenan and Ball. She claims that she read the book, but her responses indicate otherwise, or else a lack of understanding of the book. The use of the ‘Reptile’ isn’t to scare a juror into a decision. It is an attempt to re-balance the playing field, which for years, based upon misinformation and FEARS spread by insurance companies and corporate interests, has been skewed by the very principle she condemns the use of by Plaintiff’s attorneys. The use of the ‘Reptile’ narrative merely restates your clients narrative in a fashion which will allow the jurors to understand that the dangers which affected the client, affect all of us. This is a TRUTH, which a juror, once enlightened to the fact, MAY give a fair award to your client. Jurors have been so indoctrinated by the onslaught of ‘greedy attorney’, ‘frivolous lawsuit’ nonsense, that both you and your client have been prejudged before you’ve even had a chance to introduce yourself. The purpose of the ‘Reptile’ is to have jurors react on a basic level, in the same fashion they would react if they weighed and considered the actual evidence presented, without viewing through the distorted lens of corporate propaganda. (NOTE: Inasmuch as you are no longer practicing law and you are a corporate lecturer, your position is understandable as ‘Reptilian’, necessary for your continued economic survival.) Nonetheless, for those of us still pursuing justice for our injured clients, I will use every tool I have to assure that my client receives a fair verdict with just compensation for their losses!

This article is a few years old but provides some interesting insight into juries:… http://t.co/Evl4jfhSYC

I think we are oversimplifying when we say that the Reptile is disrespectful to a jury. this argument has some superficial appeal – the book it called Reptile, right? – but I don’t think it disrespects juries. Both side of a jury trial try to use fear to win their cases just like we try to use people’s base instincts and their intellectual reason to our advantage. This is a method of tapping into that fear.

I don’t want to learn too many lessons from Atticus Finch one way or the other because — spoiler alert! — that is a fictional book. Besides didn’t that guy always wear a tie even when with his kids. Weirdo, right?

It is important to keep in mind that this is not the Americans v. Soviets here. There are cases plaintiffs should win and there are cases plaintiffs should lose.

But this the point I want to make. I read all of the positions set out above. I learned something from everyone on BOTH sides and agreed with some of the arguments of each writer (and many of the comments). This happens pretty rarely on the Internet.

As a layman, I can state that one of the reasons lawyers have a “bad reputation” is because they are perceived as deceptive. Most everything I’ve read about using the “reptilian brain” to influence jurors AND the rebuttals to that approach reinforce my impression that lawyers can be incredibly deceptive.

As a layman, I have a different perspective; one which will, I suspect, be considered naive if not ludicrous. It is this: Regardless of social background, all human beings know the difference between right and wrong. To manipulate them to achieve results which may actually be wrong – and lawyers know this is necessary if they are to earn their reputations – is at the core of what stinks about the legal profession.