"We test communication by conveying a message and having the recipient understand it, be interested in it and remember it. Any other measure is unimportant." — Richard Saul Wurman, Information Anxiety, 1990

The Urgency of Now

When an important event happens anywhere in the world today, the speed with which it's disseminated via the Internet, television and other electronic media is unprecedented. Viewers will likely see an anchor person coordinating the coverage, live video from the field, animations, interactive maps, historical footage and documents, all of which are rapidly delivered in sound bites via multiple channels. As technology has changed the way we receive, process and evaluate information, the way we communicate – whether in the classroom or the courtroom – must align.

This is particularly true with Generations X (born 1966 – 1981) and Y (born post-1981), the former being raised on cable TV and video games, the latter on the Internet, text messaging, blogs, smart phones, Wikipedia and Facebook. These generations expect instant access to headlines and diverse forms of presentation.

But our multi-technological lifestyle has even permeated Baby Boomers. According to data from Deloitte, 2009 was the year that social media bloomed for Boomers, with 47% of them maintaining a profile online, the largest increase of any group from the previous year. 73% of those reported that they actively maintain a Facebook site.

Thus, it should come as no surprise that today's juror expects to be engaged and entertained quickly and through multiple visual mediums. And the price any litigator pays for not keeping pace with their expectations and high standards for communication can be deadly — disengagement. When confronted with a subject matter too tedious, complex or remote, the typical reactions are to become frustrated, to turn off — and worse, to look elsewhere for a more digestible explanation. In a courtroom, this could lead to your opponent.

Cutting Through the Haze

Making things concise, impactful and more memorable is a key reason behind the dramatic growth of demonstrative visuals and increasing sophistication in courtroom technology. We know from numerous studies that jurors will understand more and retain it longer with both visual and verbal presentations (Weiss-McGrath Report, 1994). While legal cases grow increasingly complex and cumbersome, victory often goes to the side that makes its points most readily understandable and presents its arguments in the manner and medium best suited to jurors' learning preferences today.

Technology by Design

Given the technological advances that have expanded the arsenal of tools available to the litigator, a pressing problem centers on how best to deploy them. What are the options?

Intra-firm enterprise software is used to manage the flow of information among the trial team members, allowing users to store and retrieve documents, reports and depositions. But as the case moves into the courtroom, techniques and tools can help organize and present the voluminous information.

Boards

Anything electronic is generally understood to be "technology," and this includes even the document camera or "Elmo." However, boards or blow-ups still have a place in the courtroom, and we recommend using boards for your most salient points — the ones you want to keep in front of the jury for as long as possible. Much like "Pavlov's dog response," every time that a board appears, a juror should think, "This must be important." Use boards for:

- Key Themes

- Timelines

- Maps

- Parties Charts

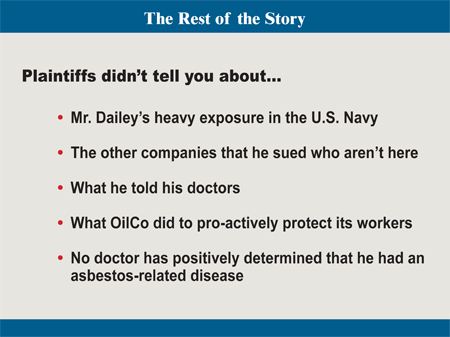

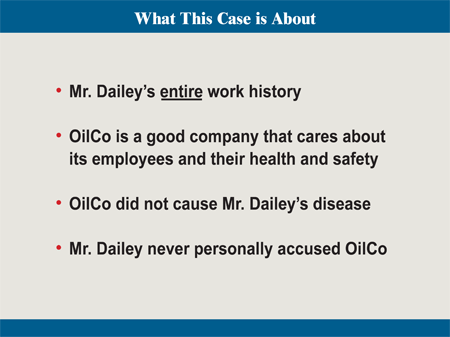

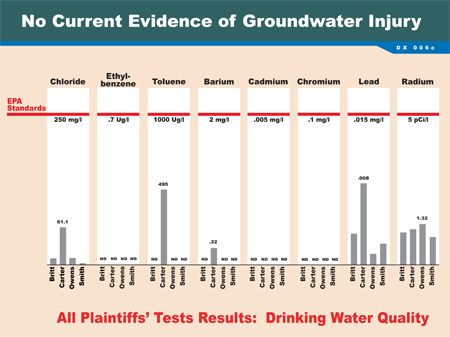

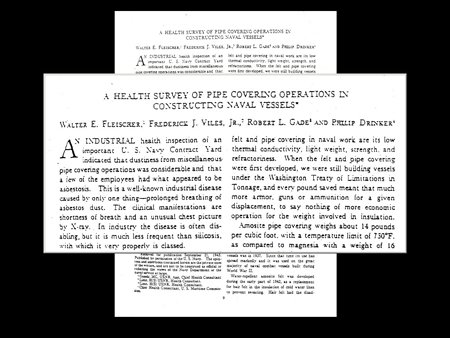

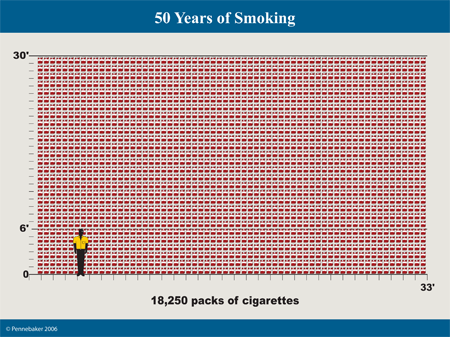

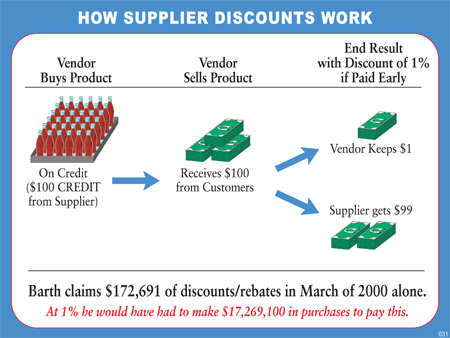

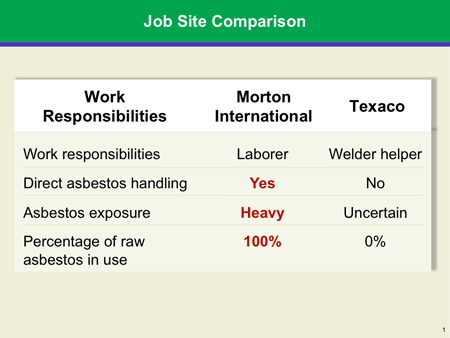

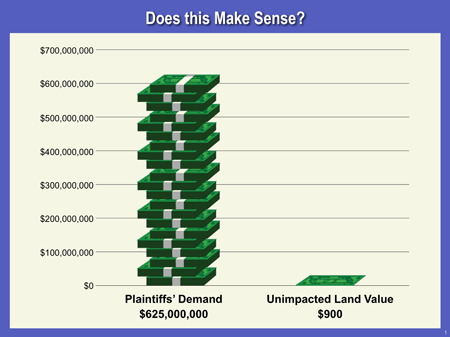

Example: The following boards were used in opening statement by the defense in an asbestos trial as a way to introduce themes or information "buckets" to the jury.

PowerPoint

PowerPoint(TM), the ubiquitous corporate presentation toolset, has become a mainstay in the courtroom. It's easy to program, easy to use, and an effective way to present information, particularly during opening statement and closing argument. But, just because PowerPoint has many presentation features (text dissolves, zooms, fades and other snazzy transitions) does not mean that one should use each and every one of them. Moreover, not everyone is adept at graphic design, and the effective display of information on each slide is an art that develops with practice.

Some important points to remember with PowerPoint:

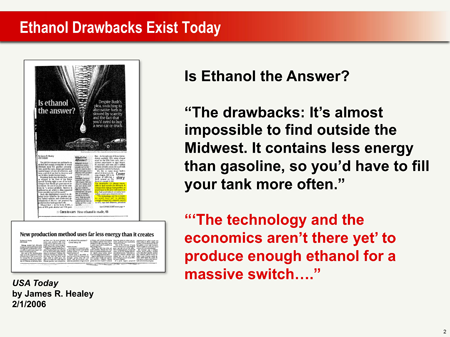

Use pre-prepared document "call-outs" in PowerPoint to ensure readability:

Builds can also be used in PowerPoint to present complex information in layers, bit by bit, so as to maximize the jury's understanding and minimize confusion, particularly with a scientific chart:

In this example, the data from each test well was brought in one column at a time. All results were at or below the red line (the EPA standard).

Timelines can be shown as a build by date.

Trial Presentation Software

Trial presentation software is the best technology to use with document intensive cases since it allows for excerpting and highlighting documents "on the fly." This interactivity makes an otherwise laborious and dull presentation more engaging and memorable to the jury, and it uses time more efficiently. TrialDirector(TM) and Sanction(TM) are two of the most commonly used trial presentation software packages. Both of these programs use non-proprietary formats and integrate well with other programs such as Summation(TM). They serve as case "portals" where documents, video, animations and graphics are organized and easily accessed during trial.

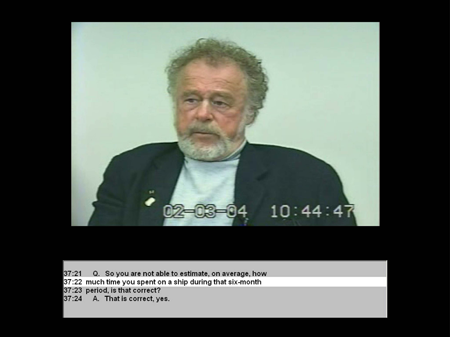

Screen shot from Sanction of a video deposition with scrolling text. Since jurors are both reading and hearing the testimony, they are more likely to retain it.

Document excerpt using Sanction or TrialDirector.

Animations

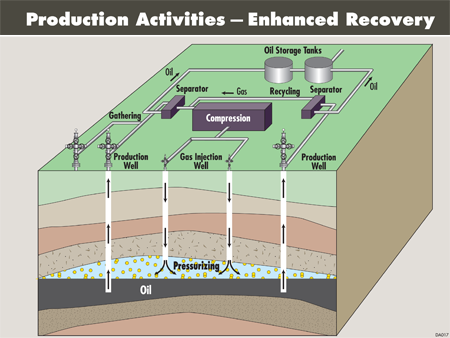

The great value in using animations is that they can help you see what you can't normally see, go where you can't normally go, and graphically simplify a complicated process. This is particularly true with abstract and complex scientific concepts such as those found in toxic tort cases. The science needs to be explained in a way that is both compelling and understandable to the jury. It should teach them about the science in small doses, while at the same time reminding them of how it fits into your case theme.

Downhole animation

Accident reconstruction

Graphics

Creating effective and persuasive graphics is a skill that combines art, cognitive psychology and communications strategy. Consider the following examples:

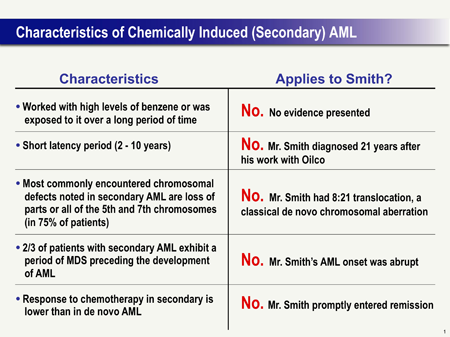

In discussing scientific studies, use a visual build to demonstrate that the plaintiff does not exhibit the typical disease profile, as shown above.

Differentiate plaintiff's lifestyle from population studied.

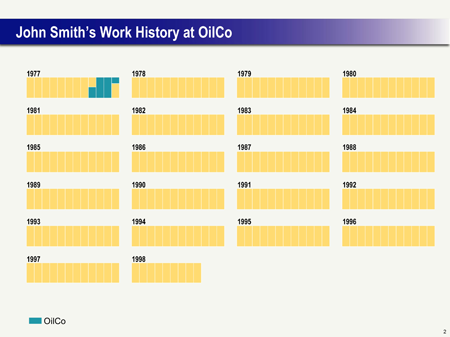

Put work history into context. The blue bars represent the number of months the worker

worked for OilCo vs. the yellow bars, where he worked elsewhere.

Economic hardship "at a glance in 1990".

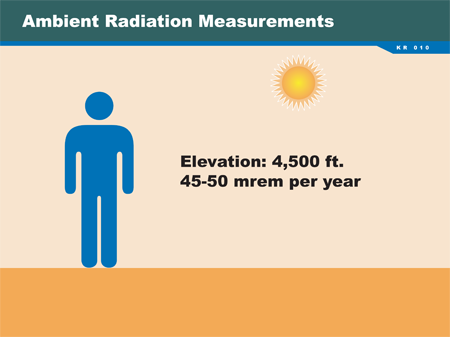

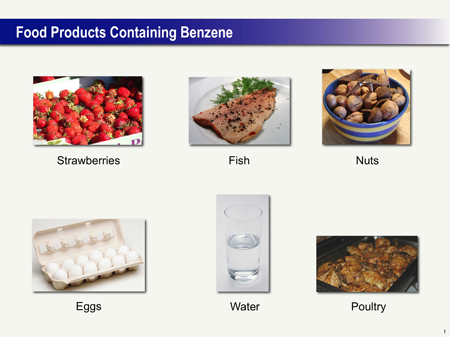

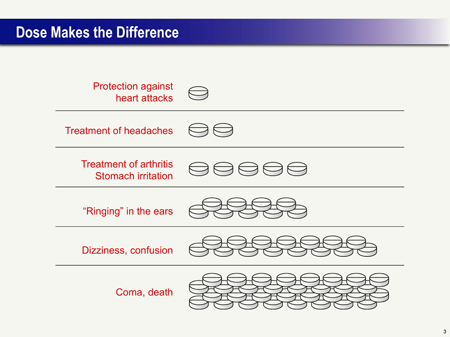

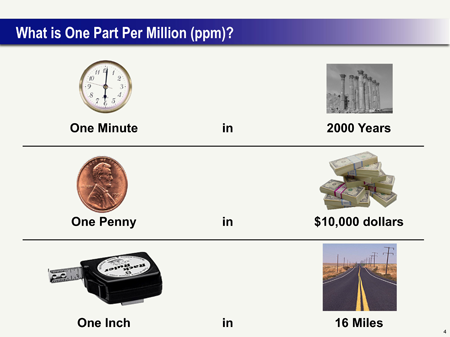

Diffuse the belief that any amount of exposure to a chemical or element can be toxic, no matter how small the dose.

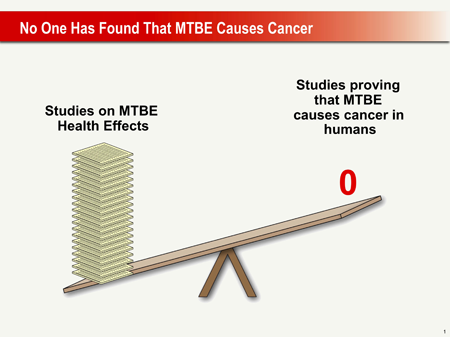

Contrast and compare data or facts to support your conclusion.

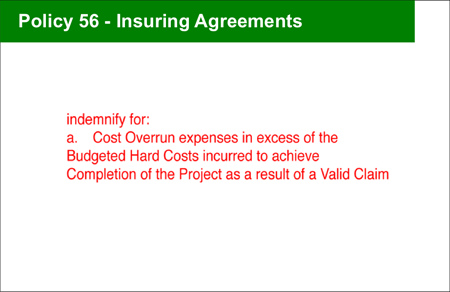

Visual schematics demonstrate process flow.

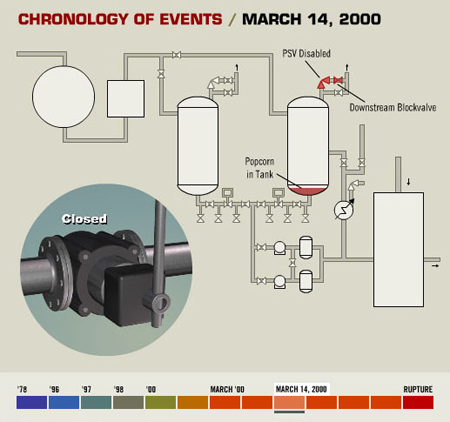

Comparison charts.

a.

b.

c.

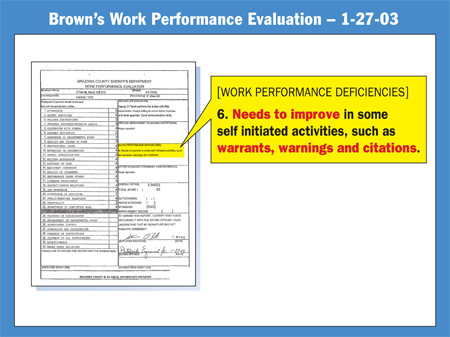

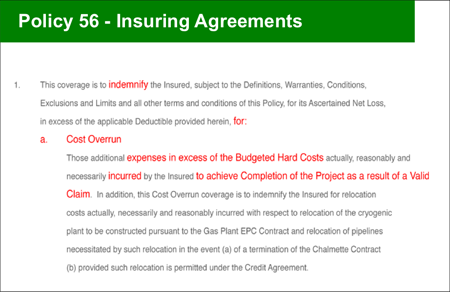

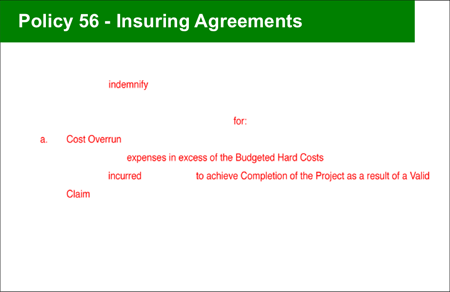

Use sequence to highlight the critical text.

Use interactive timelines to tell the story in manageable sound bites.

Use inconsistencies to attack credibility of a witness.

The bottom line: use graphics as liberally as possible to show context, comparisons and contrasts, and to otherwise visually support elements of your case. Some rules of thumb:

1. Mix your media. If every point you make is presented in the same medium the jury will soon become bored and disengage. Using color, illustrations, animation, and interactivity will help keep jurors' interest piqued.

2. Limit the number of words per slide. Anyone who has had to sit through a PowerPoint slide show where the speaker has felt compelled to read each slide word for word has experienced the true meaning of "Presentation Hell." The slide should be the shorthand device that gives the jury context to your argument.

3. Limit the slide to one message. Before preparing a slide, ask yourself, "What is the one point I want the jury to get from this?" Too often a slide becomes the repository of multiple thoughts and the jury spends its time trying to figure out the slide, rather than listening to the speaker.

Conclusion

The use of technology in the courtroom has been increasing as lawyers realize its value to today's tech-savvy jurors. It brings organization and clarity to your case, allows you to present information in a format that is visually appealing, and delivers it in easily digestible sound bites. Anything less might give your opponent an unnecessary advantage.

All trial attorneys realize that a picture is worth a thousand words. But today's technology is speaking in volumes.

References

Dombroff, M. (1983). Dombroff on Demonstrative Evidence 2, Weiss-McGrath Report by McGraw Hill, 3-4.

Susan Pennebaker, J.D. received her B.A. (1976) and J.D. (1978) from Louisiana State University. She practiced at Exxon and in Houston law firms for twelve years before joining Pennebaker Fifth Ring as a principal. She consults with attorneys on theme development, presentation strategy, jury strategy and demonstrative evidence development in complex litigation, focusing on energy and toxic tort litigation. Learn more at www.pfrlegal.com

Citation for this article: The Jury Expert, 2010, 22(2), 35-44.

Ted Brooks has done a blog post on this article: Ted's blog post

Susan- This is a good overview of technology strategy for litigation. I think the point you make that visual aids are not only helpful, but have become expected, is an excellent one.

I agree with the points in your section titled "The Bottom Line," but as I'm sure you know, it can be extremely difficult to stick to these parameters in the real world. Even some of the examples shown here venture outside of these guidelines.

It would be interesting to read why having only one theme per slide is more effective than having several, for example. Or why limiting the amount of text on a slide helps make the message more clear. And if these things are true, why do we see so many demonstratives that don't practice this?

I think we expect too much from our graphics, sometimes. Most often, if the graphic is confusing, it's because the message itself is unclear.