|

The impact of the internet on jury trials has been dramatic, opening up new avenues for both uncovering information about potential jurors for jury selection purposes and inappropriate, and potential, misconduct by jurors.[1] For jury selection, the internet provides resources with which to understand potential jurors (and identify potentially favorable and unfavorable jurors), including, among other resources, (a) social media accounts of potential jurors (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and Twitter); (b) participation in activities relevant to the case (e.g., friending, following, likes/reactions, or contact with victim-related websites/Facebook pages, witnesses, and attorneys for the parties, along with case-relevant rallies or marches); (c) comments, replies, reactions, and shares appearing on news media accounts (both “.com” and social media accounts); (d) identification or contact with critical social media entities (e.g., political, social issues, or business entities); (e) civil (e.g., bankruptcies and prior lawsuits) and criminal records; (f) product/consumer reviews; (g) political donations; and (h) online petitions. The internet has also opened up new avenues for inappropriate conduct or misconduct by jurors, such as (a) researching media coverage of the case; (b) researching legal definitions; (c) inappropriate contacting/communicating with fellow jurors, witnesses, the parties, and the parties’ attorneys; and (d) posting comments, blogging/personal journaling, tweeting, and conducting case-related polling, among other activities.

Generally, courts and professional legal organizations have held that it is appropriate to research potential jurors’ (and jurors’) internet activity as long as no direct contact is made with jurors, including “friending,” “following,” or other methods of communication.[2] In fact, some courts have encouraged such internet research, at least in terms of searching court records available online,[3] while at least one court has discouraged such activities.[4]

While many legal commentators have stressed the need to conduct internet research on potential jurors using trial consultants, private investigators, and even internet research firms specializing in gathering such information, some have suggested that attorneys (or their employees) conduct this research themselves.[5] This raises an important question: How effective are attorneys/law firms in conducting internet research on potential jurors? We decided to put this question to the test.

Description of the Study

To address the question of the effectiveness of different sources of internet research on potential jurors, I solicited participation from a number of different law firms in the southeastern United States who had conducted their own in-house internet research on potential jurors for recent jury trials.[6] In addition, an internet research firm, Vijilent, Inc., volunteered to participate in the study.[7]

Who Participated. The sample consisted of four jury lists (one from 2015,[8] two from 2018, and one from 2019) from three medium to large law firms, yielding a total of 187 potential jurors. All the jury trials involved civil cases, ranging from personal injury and medical negligence to securities law violations and fraud. The parties represented in the study included three different plaintiffs and one defendant.

What We Did. Each law firm provided the original jury list and its subsequent internet research findings in separate documents. The internet research firm (Vijilent) was provided with the original jury lists only and not the law firms’ search results. Vijilent conducted its searches in the spring of 2019 and provided its search results to the author. Neither the law firms nor Vijilent had access to the others’ search results.

Once all the search data were collected, we needed to identify potential types of information of interest. While Vijilent (and other internet research firms) provides a variety of types of information (e.g., information from social media accounts on Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, Twitter, among others), only one type of information was consistently gathered among the law firms, i.e., Facebook account information. As such, we focused on Facebook account information. In addition, given that the cases varied as to the relevance of potential information contained in the Facebook accounts, the critical measure of interest was: How successful is either research source in correctly identifying Facebook accounts for the potential jurors? All Facebook accounts identified by the research sources were checked to confirm that they were correctly matched to the potential jurors. When neither research source (i.e., Vijilent or the law firm) was able to identify a valid Facebook account for a potential juror, I conducted a brief Facebook search to confirm that no obvious Facebook account existed for the juror.[9]

What We Found

We divided the data into one of three categories: (a) no identifiable Facebook account; (b) a correctly identified Facebook account; or (c) an incorrectly identified Facebook account.[10] The general results for both research sources revealed that Vijilent correctly identified Facebook accounts for 57% of the total sample, while the law firms correctly identified Facebook accounts for 28% of the total sample.

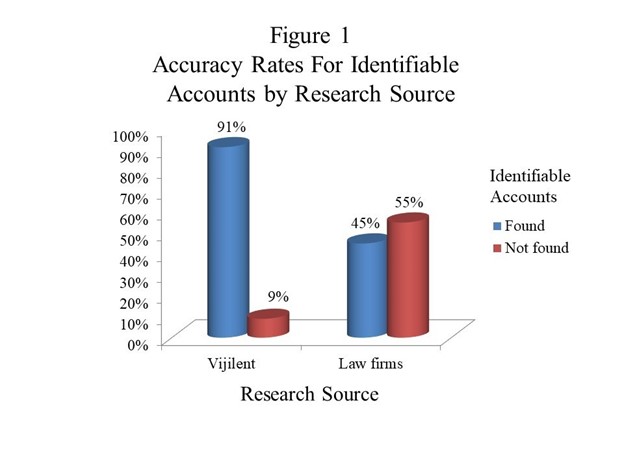

The totals for the entire sample do not give us an accurate picture of the success rates for each source since some jurors did not have Facebook accounts. To account for this, those individuals without identifiable Facebook accounts were dropped from the analyses to yield a pool of 62% with identifiable Facebook accounts.[11] Analysis of the accuracy rates for the two research sources using a general linear mixed model approach are reported in Figures 1 and 2.[12] Figure 1 shows that Vijilent correctly identified 91% of the potential jurors with Facebook accounts (“Identifiable Accounts”), while the law firms correctly identified less than one-half of the potential jurors (45%) with Facebook accounts. Based on the generalized linear mixed model results, Vijilent has a 67% higher probability of correctly identifying Facebook accounts as compared to the law firms.

|

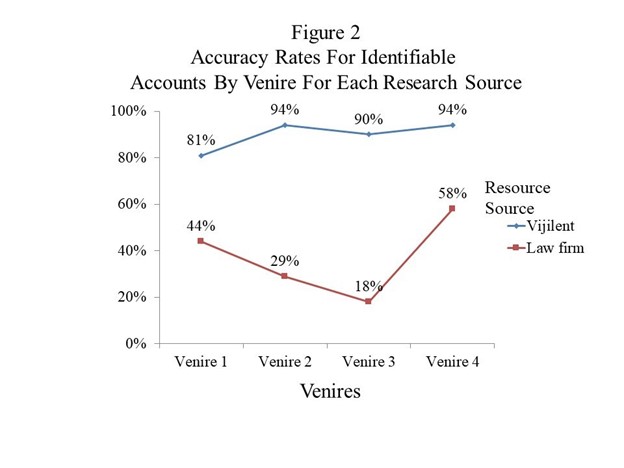

Finally, it is important to examine whether the search results varied across venires. Figure 2 shows that Vijilent was fairly consistent in its accuracy rates, ranging from 81% to 94% for identifiable accounts across venires. There was considerable variability in the accuracy rates by venire for the individual law firms, with accuracy rates ranging from 18% to 58%. However, in no case did the law firms approach the level of accuracy exhibited by Vijilent.

|

What It Means

The results of this preliminary study indicate that law firms who conduct their own internet research may be doing so at their peril. Overall, in-house law firms’ internet research correctly identified less than one-half of the identifiable Facebook accounts across four different venires, and this was also about one-half as many as were correctly identified by an internet research firm (Vijilent). While this study identifies significant discrepancies in identifying potential jurors’ Facebook accounts between in-house versus an internet research firm, it does not address the reason(s) for these discrepancies, nor does it address the scope and quality of any information acquired. Given the author’s past experience, the findings are likely a result of many factors, including (a) the use of algorithms/automated computer searches by internet search firms; (b) the differences in training between research sources (and the discrepancies in training between law firms)[13]; (c) the frequency of/experience in conducting such research; and (d) the time pressures faced by the litigants in securing this information. As to this last point, it is worth noting that internet research firms are capable of conducting their searches in considerably less time than their law firm in-house researcher counterparts.

Final Thoughts

Today’s litigation and jury selection environment necessitates that we maximize the information we know about jurors. The potential jurors’ internet footprint—and social media presence—provides an important source of information outside of voir dire. However, as the above study indicates, it is not a simple DIY task. Compounding this problem is the fact that there are no objective indicators for when all or a significant portion of the available information is discovered. This fact can lead to incomplete research fostered by time and training constraints that often surround a trial. Professional services, including internet research firms and trial consultants, can play a key role in assisting attorneys in finding answers to the questions of “what’s out there” and “what does it mean” in terms of the jurors’ internet footprints—via social media and other sources available through the internet.

Jeffrey T. Frederick, Ph.D.

President, Jeffrey Frederick Trial Consulting Services, LLC

Charlottesville, Virginia

[1] For more detailed discussions and examples of the internet activity discussed below, see Jeffrey T. Frederick, Mastering Voir Dire and Jury Selection: Gain an Edge in Questioning and Selecting Your Jury, 253-284 (4th edition, 2018). See also John G. Browning, Voir Dire Becomes Voir Google: Ethical Concerns of 21st Century Jury Selection, 45 Brief, 2, available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/tort_trial_insurance_practice/publications/the_brief/2016_17/winter/voir_dire_becomes_voir_google_ethical_concerns_of_21st_century_jury_selection/ , Retrieved 11,19, 2019; Luke A. Harle, A Status Update for Texas Voir Dire: Advocating for Pre-Trial Internet Investigation of Prospective Jurors, 49 St. Mary’s L.J. 3, 665-698 (2018); Thaddeus Hoffmeister, Google, Gadgets, and Guilt: The Digital Age’s Effect on Juries, 83 U. Colo. L. Rev. 409 (2012); Adam Hoskins, Armchair Jury Consultants: The Legal Implications and Benefits of Online Research of Prospective Jurors in the Facebook Era, 96 Minn. L. Rev., 1100-22 (2012); J.C. Lundberg, Googling Jurors to Conduct Voir Dire, 8 Washing. J. L. Tech. & Arts 123-35 (2012).

[2] See ABA Comm. on Ethics and Prof’l Responsibility, Formal Op. 466 (2014); Bar Ass’n of City of N.Y. Comm. on Prof’l Ethics, Formal Op.2012-2; N.Y County Lawyers’ Ass’n, Formal Op. 743 (2011). For court decisions approving or at least acknowledging the widespread use of internet research, see Carlino v. Muenzen, No. 5491-08, 2010 WL 3448071 (N.J. Super. Ct. App. Div. Aug. 30, 2010) (unpublished opinion); and Sluss v. Commonwealth, 381 S.W.3d 215 (Ky. 2012).

[3] See Johnson v. McCullough, 306 S.W.3d 551 (Mo. en banc 2010) (per curiam).

[4] See Oracle Am., Inc. v. Google Inc., 172 F. Supp. 3d 1100 (N.D. Cal. 2016) (judge would have allowed internet research on jurors by the parties but only if, among other conditions, (a) jurors would be allowed to reset their privacy settings in advance of such research; (b) jurors would be told that the parties would be conducting such research even though the jurors could not do any internet research on the case themselves; and (c) the parties would be required to keep detailed records of their research activities; the parties opted to forego conducting internet research).

[5] E.g., Browning supra note 1 (“where with just a few mouse clicks, an attorney can learn all about a prospective juror”); Harle, supra note 1 (“Any attorney . . . with a few clicks of a mouse, can discover the person behind the jury member.”); Hoskins supra note 1(“The advent of the internet has made attorneys everywhere into amateur jury consultants.”).,

[6] This study was conducted when I was Director of the Jury Research Division of the National Legal Research Group, Inc. I would like to thank those firms who volunteered their time and provided the necessary information for this study to be conducted. Without their efforts, there would be no study. These firms agreed to participate based on their firms remaining anonymous. As such, they are not listed here, but our genuine thanks remain for their commitment to evidence-based litigation techniques.

[7] Vijilent is an internet research firm specializing in the collection and analysis of social media and public records data as it pertains to potential jurors.

[8] The search results for the 2015 jury list were limited to social media accounts that were established before the trial date in 2015 so as to not skew the results with the appearance of social media accounts added after the original search by the law firm.

[9] Facebook accounts do not need to be registered in an individual’s real or legal name. Hence, it is nearly impossible to match all potential jurors who have Facebook accounts without Facebook providing such information—which it does not.

[10] A more detailed account of the research findings is available in our research white paper at https://www.jftcs.com/s/It-Matters-Who-Conducts-Internet-Research-on-Potential-Jurors-An-Internet-Research-Company-v-Law-Fir.pdf.

[11] This figure is not too different from surveys by PEW Research, which reports that 69% of the U.S. adult population use Facebook. See John Gramlich, 10 Facts About Americans and Facebook, PEW Research Center, May 16, 2019, available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/16/facts-about-americans-and-facebook/.

[12] An analysis using a generalized linear mixed model addressed the issues of whether (a) the research sources (i.e., Vijilent versus law firms) differed in overall accuracy rates and (b) accuracy rates differed across venires (i.e., the random effects of venire). These results are significant at the p<.001 level of significance. Details of these analyses are available from the author. The author greatly appreciates Jessica Mazen for her development of the generalized linear mixed model analyses reported here.

[13] This may be a larger issue for law firms going forward in terms of attorney competence and the use of technology as stated in Comment 8 to Section 1.1 of Competence in ABA’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct (2012) (“To maintain the requisite knowledge and skill, a lawyer should keep abreast of changes in the law and its practice, including the benefits and risks associated with relevant technology, engage in continuing study and education and comply with all continuing legal education requirements to which the lawyer is subject.”), available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_1_1_competence/comment_on_rule_1_1/.